Elite Timeline Evolution

I will get around to writing "Games I Love: Elite Dangerous" sooner or later, but in the meantime please enjoy this lovely video by Retro Games Look cinematically chronicling the evolution of the series.

I do wish they had listed all the versions used though, especially for the original game. The BBC version is obvious, and I'm pretty sure that I recognized shots from the Electron, NES, Atari ST/Amiga and Archimedes. There's one with a lot of colour artifacts that makes me think it's the Apple II but there's a few I'm not sure of at all. Definitely no Speccy version, sadly.

Anyway, it's a very loving tribute to some of my favourite games. Make sure you watch it to the end.

Games I Don't Love: Frontier: First Encounters

(Frontier/Gametek 1993. DOS)

Nine years passed between the release of the original Elite and that of its sequel, but we only had two years to wait for the next entry in the series. I had caned Frontier: Elite II on the Amiga, but now I was at college studying Software Engineering and had reluctantly acquired a PC, ostensibly to do coursework, but of course I wasn't going to pass up the opportunity to explore the world of DOS gaming. My 486 SX 25, with its 4 meg of RAM and 120mb hard drive was hardly a powerhouse even by the standards of the day, but above running Turbo Pascal and Visual Basic for college it could do a respectable job with stuff like Wolfenstein 3D, and could just about cope with Doom, albeit with some slowdown and hard-drive thrashing.

When it was announced that the third game in the series, Frontier: First Encounters, would feature full texture-mapping of its 3d models, as well as planets with actual terrain instead of the smooth pool-balls of its predecessor, of course I was excited. That it would be a PC-only release was sad but not unexpected, these being the final days of the venerable Amiga. The requirement for a math-coprocessor was a bummer, though, as that was something the "SX" flavors of the 486 processor lacked. Still, I was living at home rent-free, so I set about raiding piggy banks for unspent birthday money and checking down the back of the sofa. (I was one of the last generations to receive a government grant to pursue higher-education in the UK, and while it was fairly paltry I can't honestly claim that none of it went towards this most noble of causes as well. But it was a long time ago and my memory is hazy.)

PC duly upgraded - fortunately it was a drop-in replacement for the CPU that was already there and didn't require a new motherboard - release day came and I breathlessly installed and launched Elite 3.

It was technically impressive all right. True enough, all the spaceships and stations now had textures applied to them, giving the impression of more detail, and the planets now featured mountains, coastlines, and valleys that you could pilot your ship down. That was cool. And it was more Elite! Sure, space was still that obnoxious shade of blue, but there were more mission types, more spaceships to pilot, and the return of the alien Thargoids, nominal antagonists of the first game that had been suspiciously absent, bar one well-hidden easter egg, in Elite II.

I dove in, and while I did play it for many hours, something niggled at me. Several somethings actually. Those texture maps and fractal landscapes I was so jazzed about? They might not have been possible on my Amiga, but man, were they ugly! Those nice clean polygons ruined by a smudgy low-resolution mess, like they had been badly vandalized, graffitied by a teenager with a spray can. I realized then that the previous game had a minimalist beauty that was perhaps less realistic but somehow felt more real.

On top of which, First Encounters was buggy. Crashes were all too common, of both your real-world computer and your in-game ship when entrusted to an autopilot that liked to slam it into the sides of space-stations. This being some years before digital distribution became commonplace, providing patches for the game post-release was a matter of offering them on floppy disks to affected customers, and I dimly remember my copy having one such disk in the box already. It would later transpire that publisher GameTek was on the verge of bankruptcy and forced Frontier to release the game in an unfinished state in a desperate attempt to bring in some revenue, much to the chagrin of David Braben and his team.

None of which is to say that I didn't enjoy my time with First Encounters. I did, but I was left wondering what could have been, with just a little more polish and some different creative direction. Still, it was a much beloved series of games, so surely Elite IV would be along soon, right?

#gamesilove #gamesidontlove #elite #frontier #frontierfirstencounters #msdos

Getting Off Amazon

It's been no secret for a long time that Amazon is a grossly unethical company but I'm as guilty as anyone for letting convenience guide my shopping instead of my conscience. Like many, Jeff Bezos choosing to kiss the ring of Donald Trump was the last straw for me, and I've set about something that I should have done years ago, by de-Amazoning my life as best as I can, cancelling Prime, refusing to order from them, and curtailing any grocery shopping I might have done at Whole Foods. (We don't have any Alexa devices, thankfully, though having another evil megacorporation listening in on us is probably just as bad and a discussion for another time.)

But a lot of people probably don't realize just how deeply entangled that company is into their everyday lives. At the time of writing, Amazon Web Services - their cloud hosting platform - accounts for about 30% of the total worldwide cloud infrastructure market share, with Microsoft's Azure lagging behind at about 21%. It's estimated that something like 74% of Amazon's total profits come from AWS.

Amazon's core business isn't about selling you crap and delivering it next day. That's just a fun little sideline. It's running the websites and services that you probably interact with multiple times a day, silently and invisibly.

There ain't a lot that any of us can do about that. If your banking app or favourite social network is running on AWS you'd probably never know it. But developers with any say in the matter can at least try to support alternative options.

One advantage of AWS is that it's relatively cheap, at least for small projects. I've used AWS a lot in my day job, so when I was setting up this site, determined that I neither wanted nor needed a heavy CMS like Wordpress and was happy with it being static HTML, I decided to throw it into an S3 bucket (Amazon's cloud-based file storage), point the domain at it, and bam, job's a good-un. It wound up costing me about seven bucks a month, which seemed reasonable at the time especially compared to some other hosts I had used in the past.

Anyway, even paying those seven bucks leaves a bad taste in my mouth, and after seeking recommendations on Mastodon I've moved this site over to Porkbun. It was fairly quick and easy and, even better, only costs about $30 for the whole year.

(This is not necessarily an endorsement of their service btw. I've only been a customer for a few days. It's been smooth sailing so far, but other options are available, do your own research, etc etc.)

Did I mention that I added the ability to upload to S3 to my SuperSimpleSiteGenerator? Well I don't know if I'll rip it out as a matter of principal or if anyone else would find it useful. I suppose it'll break eventually as a result of an API change and I won't have the desire to fix it. Anyway I'll probably be adding FTP support soon. Maybe you'd like to use it yourself, if you want a quick and lightweight way to spit out blog posts with little-to-no server-side shenanigans required. Alternatively here's a nice list of options curated by Alan W Smith.

Games I Love: Frontier: Elite II

(Gametek/Konami 1993. Played on Amiga.)

Ignoring rereleases such as Nintendo's continual repackaging of Super Mario Bros et al, few games saw as many official ports over such a long period as the original Elite. Released in 1984 on the BBC Micro, it lived well into the 16-bit era, with versions for the Acorn Archimedes, PC and NES all coming out in 1991. More powerful computers meant better framerates, solid 3D graphics and more custom missions, but the core of the game remained essentially unchanged. It wasn't until 1993 that a true sequel arrived in the form of Frontier.

By then I was rocking a newly acquired Amiga 1200, and Frontier was just the killer app to justify my defection from the Atari ST (which did get a port, but it ran slooooowly). As soon as the intro cinematic started, all rendered in-engine and including nothing that you couldn't actually do yourself in the course of the game, I knew I was in for a treat. Check it out:

I still think it looks cool today and really sets the scene for the kind of deep-space adventures that await you. (Though I don't know why the ships bob up-and-down like rowboats on the ocean.)

Although keeping the same basic gameplay loop of flying around, trading between planets, fighting pirates and upgrading your spaceship, Elite II brought an unprecedented level of realism. Solar systems no longer consisted of a single star, planet and space-station, waiting patiently in space for you to visit. Now there were binary star systems, gas giants, icy moons and a variety of different orbital outposts, all of which moved through space according to some convincing orbital mechanics. Planets could be flown over and landed upon, whether or not they were populated with starports and cities. (That these were rendered as a handful of grey cubes didn't matter one jot.) One of the starting positions found you parked on the moon of a gas giant, and it was a joy to simply sit and watch it rise over the horizon while the wind howled around my cockpit.

Where once you were confined to a stock Cobra Mk. III, now with enough capital you could purchase a range of ships from tiny little shuttles without even room for a hyperdrive to enormous, lumbering space-freighters. As well as the trading, piracy, bounty-hunting and asteroid-mining of the original, a variety of mission types, from simple deliveries to risky assassinations, provided ample opportunities for a young commander to earn that cash.

It wasn't simply the planets that moved realistically. Your ship was now subject to proper Newtonian physics, whereby pointing in a direction and firing your engines would send you off in that direction until you applied the opposite force. No longer could you turn on a dime in pursuit of an enemy, and the joystick-focused control of the original game was out in favor of a mouse-and-keyboard approach to orienting your ship. This insistence on realism, while admirable, unfortunately turned dogfighting from a fun Star Wars-like affair, to a dull jousting match where you and your opponent lined up with each other, firing lasers and accelerating before flashing past one another in the blink of an eye, flipping over, thrusting, and repeating the process until one of you died. Later in the game, when you acquired larger, less agile ships with gun turrets that could be manned by AI crew members, combat became a matter of sussing out your opponent and deciding whether to flee, or wait for them to be automatically turned to space-dust by your defenses while you sat back and watched.

FTL travel was limited to flipping between star-systems. Travel across those systems to get to your destination occurred at realistic sunlight speeds, which in practice meant setting your autopilot and hitting the "fast-forward" button to accelerate time until you got there, sometimes passing in-game days or weeks in the blink of an eye.

To this day, then, it baffles me that a game which prides itself on its scientifically accurate portrayal of interplanetary travel would choose to render the omnipresent background of space as blue instead of black. Was the intention to suggest nebulae and the like that the platform didn't have the power to render in detail? Whatever the reasoning, it was a partly immersion-breaking choice for me, that bugs me to this day. In fact, I used to play it with the brightness on my Commodore monitor turned right down in order to get space as close to black as possible while still being playable.

I may not have put as many hours into Elite II as I did the various incarnations of its predecessor, and I can't honestly tell you if I made it to Elite combateer status, though I know I did own the largest ship in the game and was making bank hauling vast quantities of expensive cargo between star systens. For all its faults, though, it's still a formative, fondly remembered game that presented an immersive vision of space-exploration that to this day has rarely been beaten.

Games I Love: Elite

(Acornsoft / Firebird 1984. Played on ZX Spectrum and Atari ST)

Christmas 1985, I'm about to turn ten years old, and Father Christmas has left a 48k ZX Spectrum for me under the tree. I was delighted but a little surprised, as it wasn't something that I had asked for. Clearly it was a gift for my dad as much as me. He had bought a Spectrum over a year prior, but by getting me my own he would finally be able to use the thing without having to pry me off of it with a crowbar.

Alongside the Speccy was a large, black box with a bright yellow crest on the front and the word "Elite". This was a wonderfully tactile box of delights, containing the game on cassette, a thick manual, a novella that fleshed out the game's universe, a poster displaying all the different spaceships one might encounter, and a curious lump of plastic called a Lenslok.

Lenslok was a copy protection mechanism. When the game was loaded it would display a garbled mess of blocks and wait for an input. You would take the Lenslok and put it up to the screen. Looking through it would "unscramble" the image and allow you to read a code that, when entered, would start the actual game.

It was certainly ingenious, though its flaws were obvious. Should you lose or break it, your game would be unplayable forever unless you could somehow source a replacement. Plus, although there was an option to adjust the size of the image to better align with the plastic lens, some sizes of screen were simply incompatible with it. It was only ever used for a handful of titles and many of those scrapped it in later re-releases.

When I finally loaded up Elite and got past the copy protection... Well, I hated it. I had no idea what to do. Up until now, games had presented fairly obvious and intuitive goals. Shoot all the aliens. Collect all the keys. Here I was presented with an impenetrable maze of menus and keyboard commands. I could launch my spaceship all right, turn around, crash into the space station, but the rest seemed beyond my grasp. I fiddled with it for ten minutes that first day before putting it down and playing something more accessible. We already had a load of (mostly pirated) games. My dad didn't care for them (except for Heathrow Air Traffic Control, which seemed interminably dull to me), so they all went in my room. I do remember loading Elite up again at least once just to play the "use the Lenslok to unscramble the code" game, then turning it off again straight away.

I don't know how long it was - weeks or months - before I decided to knuckle down, read the manual, and try to figure this game out. It wasn't long before the scales fell from my eyes and I realized what a wonder Elite was. Here was a game that dropped you into a spaceship with just a single laser and 100 measly credits to your name, gave you a pat on the back, and sent you out to make your fortune and reputation as an Elite space combateer by whatever means you chose. You were free to trade, smuggle, bounty-hunt and pirate. The spaceships, planets and stations were simple wireframes that moved at a single-digit framerate, but that was irrelevant. No game had ever felt so real. I wasn't controlling Miner Willy or Monty Mole. I was me. A much cooler, futuristic space-adventurer version of me.

As I played I began to get good at it. I was figuring out the best items to trade between neighboring planets of different economic types, using the profits to upgrade my ship with deadlier weapons and defensive capabilities, and honing my dogfighting skills against pirates and deadly alien Thargoids. And when I was having a shit time at school, I could run home and immerse myself in a world where I was competent, powerful, and (I imagined) respected. Even when I wasn't playing it, I would fantasize about waking up one morning to find a fueled-up Cobra Mk III conveniently parked in my back garden, waiting to take me to a new life among the stars.

I did, eventually, achieve Elite status, a feat requiring the player to defeat some 6400(!) enemies in combat. Then a few years later I upgraded to an Atari ST, and was excited to start the journey over again on my futuristic new 16-bit computer. The ST release of Elite featured solid 3D graphics and a framerate that was silky smooth compared to any of the 8-bit versions. I enjoyed the new docking and launch sequences that gave you a glimpse of a hanger inside the space station containing other parked ships, and the way the docking computer would actually fly your ship (accompanied by a chiptune rendition of Strauss The Blue Danube, a-la 2001: A Space Odyssey) rather than just teleporting you to your destination like the Speccy version. Some of the colour choices seemed a bit garish though, and I was disappointed that exploding ships seemed to just disintegrate into pieces. The Spectrum version used the simple but effective technique of drawing a solid red circle for a frame or two to simulate the flash of an explosion, which was far more satisfying. But these minor quibbles didn't stop the ST version from consuming many more hours of my teenage life, though not quite as many as the Spectrum one, and I'm not sure I ever made it to Elite.

Elite originated on the BBC Micro, but I didn't know anyone who had one of those at home. They were expensive, and seemed mainly fit for boring educational purposes, lining the walls of our high school computer lab. It received a ton of ports through the 80s and 90s though, including a surprisingly capable version for the NES. And there are the sequels, of course, but I'll come back to those. They add much but aren't as accessible as the original. If you want to try it today you can fire up an emulator for your 8- or 16-bit computer of choice and almost certainly find a port for it. (The Acorn Archimedes version is particularly well thought-of.) Or, if you prefer something with more modern graphics but the same classic gameplay, Oolite might be just the ticket. But the monochromatic slideshow of the Speccy version will always have a special place in my heart. A special place only accessible via application of an awkward, easily broken plastic lens.

Games I Love: Defense Grid

(Hidden Path Entertainment, 2008. Played on PC and XBox 360)

I'm not sure what this says about my personality. Possibly something unflattering. But while I like playing an active protagonist in a video game as much as the next guy, if I can find a way to say, trick a zombie into walking off a cliff rather than shoot it in the head, or lure an opposing army into an ambush rather than engage it in an all-out assault, I find it much more satisfying. For example, I always enjoyed building elaborate defenses for my settlements in Age of Empires and watching my opponents dash themselves against them, or carefully placing traps in Dungeon Keeper for the hapless heroes to bumble into.

Is it the abdication of responsibility that appeals to me? I can't be blamed for killing all of those soldiers - they did it to themselves by trying to attack me! Or does it just make me feel clever for having set up a mechanism that allows my victory to play itself out while I sit back, sip my drink and observe the carnage?

Whatever the reasons, the whole point of the tower defense genre is to satisfy that particular impulse. Waves of enemies march on your base, and it's your job to cleverly arrange the available defenses to ensure that the horde is destroyed before they can overwhelm it. It's a simple enough formula that depends on the careful balancing of enemy types, towers and their upgrades. For my money no other tower defense game has gotten this so right as Defense Grid. (Or Defense Grid: The Awakening if you're nasty.)

Set on a distant planet, far in the future, Defense Grid tasks you with fending off an invasion of aliens intent on absconding with the valuable "power cores" that are found on every level. When they enter the map they will follow the shortest available path to the power core housing, grab one (or more on later levels), and then make their way to the exit, either back the way they came or by a different route if the exit and entrances are not in the same place. If an alien is destroyed while carrying a power core, it is dropped and begins to slowly float back to the housing. Dropped cores can be snatched up again if they don't reach the housing in time, so allowing one to be carried even part way along the exit route can be fatal, as aliens can end up "relaying" it out the door. Resources with which to build or upgrade towers are earned by destroying enemies but also earn a kind of "interest" as long as they are not spent, and there are cores in the housing, so it is your best interest not to overspend but to find a setup that requires the least number of towers. (The amount of cash earned also affects your final ranking on each stage, so even if you manage to see the aliens off without losing a core, that elusive gold medal may still be out of reach if you were too much of a spendthrift.) Defense Grid encourages experimentation, allowing you to hit a button to rewind to an earlier checkpoint at any time should things go south.

The aliens come in numerous varieties that require the player to carefully plan their tower choices. Swarms of grunts are best taken out with inferno towers that can spray flame across the whole group. Shielded enemies are resistant to heat-based weapons like lasers and infernos but weak against projectiles, so machine guns and the slow-firing but destructive cannons are your friends. Some are cloaked and can't be fired upon at long range. Others are "carriers" that drop a gaggle of smaller enemies when destroyed. And some levels also feature flying enemies that follow their own path and can only be targeted by a small subset of towers.

It's not a game that will tax your 4090ti but its ruined bases and futuristic industrial zones have aged quite well, and the friendly AI that guides you through the early stages and provides running commentary on your battles never becomes annoying. But it's the pitch perfect balance of enemies, towers and interesting level design that make it a classic of the genre, and one that I enjoy coming back to over a decade and a half later just to try and mop up those last few challenge stages. And there's nothing more satisfying than getting your setup just right, sitting back, and watching the mutant alien scum fall one-by-one before your cunningly designed defenses.

(All of the above also applies to Defense Grid 2, by the way, which is basically the same but more so.)

Minty Fresh

If you can read this (which you clearly are), it means that not only have I successfully installed Linux Mint on my main desktop machine, but I've also got a working C#/DotNet dev environment on it. Something that, I must admit, I assumed would be a lot harder than it actually was.

I've dabbled with Linux on-and-off for years and found the idea of using it as a daily driver appealing, but in the end always shied away from making the commitment for one big reason. My impression - and until very recently it was a correct one - was that Linux, while great for serious work, was not a great platform for gaming, with poor driver support and only a few titles shipping with Linux builds.

All that changed when I bought myself a Steam Deck. By golly I love that thing. It plays almost everything I've ever thrown at it, and the few games that didn't work 100% right away were quickly fixable. It has freed my backlog from the desk that I spend far too much time sitting at during the week anyway. And underneath the game launcher interface that it boots into, it's actually a fully-fledged Linux PC shrunk into a handheld shell, which can run the vast majority of Windows games via a Valve-developed compatibility layer called Proton, which miraculously translates Windows API calls in real time with surprisingly little performance impact. In some cases, because it's using Vulkan as its graphics backend instead of Microsoft's DirectX (and Linux itself tends to use fewer resources than Windows), some games may even run better under Proton than they do natively. No, it's not entirely perfect. For example, Some online multiplayer games implement anti-cheat mechanisms that take offense to being made to run under Linux. But those sort of games aren't really in my wheelhouse anyway.

So with that final hurdle out of the way, Windows 10's end of life date approaching, and Windows 11 looking to be even more bloated and full of ads I decided it was time to make the leap. I've still got some work to do to move everything over, such as my Plex server, but so far it's all going much more smoothly than I anticipated. Yes, I'll be keeping Win10 around in a dual-boot setup for the time being. Linux is a little behind as far as VR support goes, but I look forward to the day I can nuke that partition for good.

So has The Year of Linux on the Desktop actually arrived? Distros like Ubuntu and Mint have done a lot of work to take the pain out of setting up a new installation, but I'd still say that it requires a tad more technical nous than Windows or MacOS. Then again, maybe TYOLOTD has already been and gone. My wife uses a Chromebook, and ChromeOS is essentially just Linux with a super-easy UI on top and tight Google integration. And due to its proliferation as an embedded OS for things like streaming devices, game consoles etc etc, most of us are already Linux users without even realizing it.

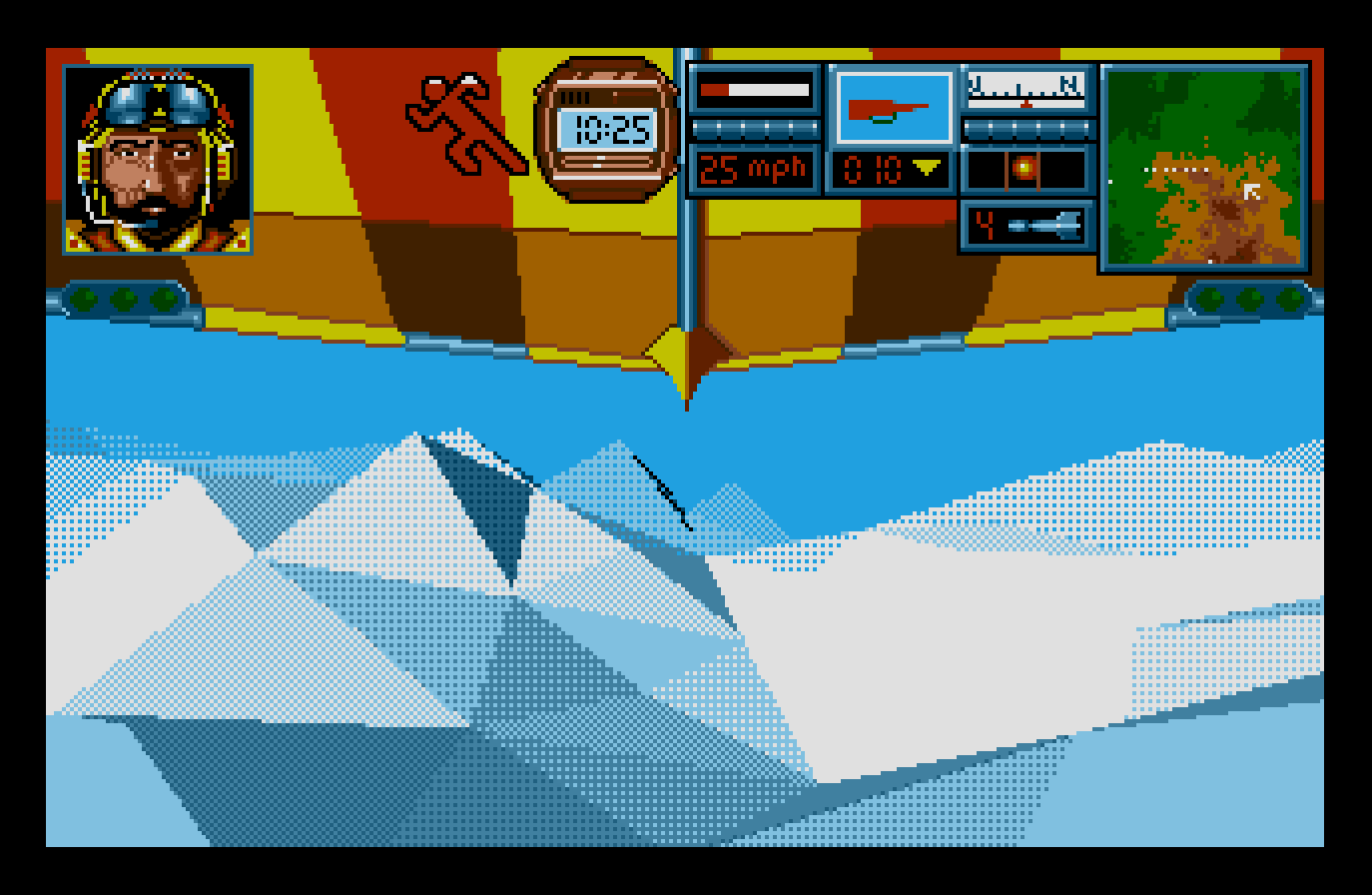

A Sense of Place: Midwinter

(1989, Maelstrom Games, played on Atari ST)

The first in a series of posts about my favourite virtual spaces.

I've been hunted from one end of this island to the other. I've been shot at, bombed, almost collapsed from exhaustion and just barely evaded capture in my mission to overthrow the dictator who has taken control of this frozen land. I've spent days in hiding, recuperating from my wounds before putting my skis on and heading back into the frigid wilderness. Now, arriving at a cable-car station, I am allowed a few precious minutes of solace. Nobody can touch me while the gondola makes its way slowly up the mountain. All that's required of me is to sit and watch the scenery, and the pylons that loom out of the fog then disappear behind me like friendly giants.

Midwinter wasn't the first game I played with solid 3d graphics, but instead of spaceships or abstract flat-walled mazes, this felt like a real-world environment. Setting the game on a frozen island was smart. Its undulating snowdrifts and craggy peaks could be convincingly rendered from just a handful of polygons and a limited palette, and the draw-distance-limiting fog was a technical necessity that only added to the sense of atmosphere. The sequel, "Flames of Freedom", was set on a lush tropical island but failed to pull it off as believably.

That the cable-car journey took a couple of minutes during which time you, the player, could do nothing other than look out the windows of the gondola... that it could, in fact, be quite boring... made it all the more real, and was something that I don't think I'd seen in a video game before. Something about the mundanity of taking what was effectively public transport from one part of a virtual world to another appealed to me, much like riding the bus around the cities of Mercenary III. (And the taxis in later Grand Theft Auto games, for that matter.)

I was never able to complete Midwinter the "correct" way, by traveling the island, hunting important characters, using your knowledge of their relationships, friendships, and feuds to recruit them to your cause. I did, however, discover a shortcut which could end the game without requiring you to ever have to talk to a single NPC. Simply make it to the top of a mountain, use the hang-glider to fly over the enemy's defenses and into the heart of their base, and blow it up with dynamite. But the best part was taking the cable car to get there.

On GameJams and People! Panic!!! (Ludum Dare 54)

You might not think so, from looking over my itch page full of wonky games, but I've worked in the software industry for over 25 years, mainly in the realm of boring grown-up enterprise stuff. I've been quite fortunate in that crunch - those periods where a hard deadline is approaching fast and the team has to put in extra hours to try and meet it - is something I've experienced only a handful of times. It seems that the tide is turning against it, as study after study shows (shock!) that driving your best and brightest to exhaustion is ultimately self-defeating and destructive. Who'da thunk it? All the free pizza and back-slapping "well done's" in the world can't give you back the time that you've lost, nor undo the impact on your relationships from spending long long hours at the office.

So why do I enjoy game jams so much when they are effectively self-inflicted crunch that you don't even get paid for?

In 2018 some friends invited me to take part in the annual VR Austin Jam. Taking place over a single weekend in the event space at the AFS Cinema, we had just two days to produce a VR-based something. I remember it being a mentally exhausting weekend where we barely saw sunlight, but there was also a tremendous energy about the space, and it was as almost as much fun seeing the other teams' projects evolve over the course of the two days as it was building our own. Our game, Flatland VR is more of a proof-of-concept than a full game, given that it consists of a single level that can be completed quite quickly, but I'm proud of what we achieved and I still think that it's an interesting concept that could have been taken further.

The next day I was pretty fried and wished that I had taken the day off of work, but there was a real sense of esprit-de-corps among the jammers. We had come together and made something cool, sharpened our skills, learned important lessons about scope and genuinely had fun. A short sprint can be an invigorating thing, though not sustainable. The sense of enjoyment would have faded pretty rapidly had it not been constrained to just a couple of long days. There was some talk of continuing the project and fleshing it out into a full game, but it didn't come to much beyond some minor bug-fixes.

VR Austin Jam returned the following year, and the same group of friends got together to enter. This time I brought along an idea I'd had for a VR game that emulated the vector-based graphics of the likes of Battlezone and Atari Star Wars After an equally exhausting weekend, the result was VekWars. This one I felt a particular sense of ownership for, given that I'd brought the original idea to the table, and I felt that there was an obvious route to completion from the original jam version, so I resolved to keep working on it, and it's now available as a paid app on both PC and Meta Quest. I still don't consider it entirely "finished" and I'm a little disappointed that I haven't managed to get an update out in quite a while, but it's absolutely not abandoned. I'll write more about its development in due course.

The 2020 VR Austin Jam was a bit of a weird one. We were deep in the COVID-19 pandemic and public gatherings weren't happening, so it went (appropriately) virtual. Thanks to the missus for offering to take care of the kids, I ended up getting a hotel room and working from there distraction-free, though again with same team, coordinating over Discord. It was still a worthwhile experience and The Vrd Dimension is the best-looking and most technically accomplished jam game I've worked on, but I'm maybe a little less fond of it due to the circumstances of its creation. It did, at least, provide some positive social interaction - albeit virtual - during an isolating and anxiety-ridden time.

I also took part in the annual GBJam a couple of times. This is an online, seven-day event to produce a game in a "Gameboy style". The requirements aren't hard-and-fast, and there's no need to make a game that actually runs on a Gameboy, but it should at least give the impression of one that could have appeared on the platform. Jocelyn Undergoes Many Perils and Super Laser Arena 9,000,000,000 came out of that one, and were enjoyable to create in a different way. They were both solo projects, so there was no social aspect, but that did mean that I had total creative control (for better or worse). The seven-day deadline meant that I was working on them around my work and family commitments, so they were less intense than an in-person weekend, but also provided some real motivation and focus. I'm proud that both of those games feel "complete" in a way, rather than just demos of larger games that never were. (Though I do have an expanded, colourized version of Jocelyn that's been 85% finished for bloody ages now.)

I'm always suspicious of mental health self-diagnoses but I'm going to hypocritically suggest that I might have some variety of ADHD. My folder full of unfinished game projects is testament to periods of intense focus that then fizzled out, resulting in my focus wandering off in search of some other source of dopamine. Opening that folder often leaves me depressed and frustrated with myself and my inability to see projects through to completion. GameJams provide the pressure to maintain focus while still operating across a short-enough timespan that I'm usually able to get to the end before the novelty wears off. I get the rare joy of actually completing something without the months- or years-long slog of a larger videogame project.

Sadly Austin VR Jam is no more, the 2020 virtual edition having been the last one. I still see that same group of friends from time to time, but recently we were talking about how much we missed VR Austin Jam and that we should all do another, non-VR related one some time. One of our number offered to host at his house so we could tackle Ludum Dare 54, and we convened there over the weekend of September 30th/October 1st 2023 to make what became People! Panic!!!.

The theme of LD54 was "Limited Space", and our host Paul came up with a scenario that we could all identify with - feeling anxiety when in a busy, crowded space. In its initial conception the player would find themselves in a series of crowded environments - a concert, a busy shopping mall, a sporting event - and have to make it to the exit before their anxiety got the better of them. There would be a feeling of being crushed from both sides by an ever-encroaching mass of bodies, and a nightmare-like atmosphere whereby escaping one environment would immediately segue into the next.

I initially imagined the throngs of people who would flood into the room as having a pre-defined "shape". Although each individual would be subject to their own physics, perhaps there would be a form to the crowd in which they walked. A form that could be messed up by the player running into them, yes, but also one that could provide a puzzle element. Like spotting where two jigsaw pieces would collide and finding the optimal path through them.

That idea might have worked but would have required a more carefully curated approach to our level design and therefore more time, so we decided to implement a more simplistic spawning behaviour whereby people would flood into the room via doors and wander around somewhat randomly. A simple mechanic that we managed to get working pretty quickly. I knocked up a big square room with some doors using tiles from another old, unfinished project, we made some ugly blobs for the player and "enemies", and by the end of the first day we had the basic gameplay loop down. Enter the room, get to the other side, avoid the people flooding in from either side. Each time you collided with one you would be knocked back a little and your "anxiety meter" would increase, resulting in a "panic attack" and game-over.

The second day wasn't quite as productive as the first. We added a "sprint" function, improved the ui, and replaced my tiles and the people blobs with some nicer, more colourful sprites. We didn't get around to implementing rooms that looked like real-world environments, so instead made a bunch of abstract levels with obstacles in the middle and people "spawners" in different locations. The concept still works though, and I laughed like a drain the first time I saw the Doomguy-style "panic level" emoji face in the corner. Our regular sound person wasn't available this weekend but his last-minute stand-in did an admirable job in creating crowd ambiance that becomes more distorted and chaotic as your sanity degrades.

For a quick five-minutes of amusement it's kinda fun, though play for any longer than that and its shortcomings become apparent. Really the "people" that you run into are more like particles that move at a set rate, bash off of each other (and you), and run head-first into walls. There was some attempt to shape their behaviour. The spawner doors have a range of configurable speeds that they can apply to the new humans that they birth, and there are invisible zones in some levels that are "attractive" to a random smattering of people and cause them to congregate there as though they were a point of interest. (Those might have worked to sell the "real-world environments" theme if we had gotten there.) Conversely, there are certain zones that they are supposed to try to avoid, such as around the exit door, though it's clear that those weren't entirely successful as they'll often get stuck there, making it difficult to escape the level. We didn't want to have a hard "force field" that they'd bounce off of. Instead, when they enter one of those zones, they will pick a location elsewhere on the level to head towards, but some of the time they'll get stuck on the scenery or ricochet off of each other and never make it out of the doorway.

I doubt we'll continue to work on it, but if we were, I'd want to work on the aforementioned environments, maybe emphasize the "nightmare" scenario a bit more, make the people wander around a bit more realistically such that they don't slam into walls, and add more customization to how they spawn and behave in order to introduce some more interesting scenarios.

Actually, the concept actually reminds me a lot of Disc Room which uses different challenge conditions for each area to keep things fresh and get more mileage out of a limited set of rooms. Perhaps a progression system based not just on getting to the exit but, say, surviving 30 seconds or bumping into fewer than 3 people would add a more interesting layer of challenge to proceedings.

Still, it was a good time, it was nice to get (most of) the band back together, and, most importantly, we made a thing that exists. What's better than that?

Play People! Panic!!! in your browser!.

#gamejams #mygames #vraustinjam #flatlandvr #vekwars #thevrddimension #vr #ludumdare #jocelyn #sla9b #peoplepanic

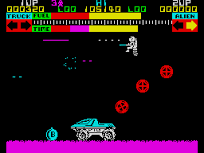

Games I Love: JetPac

(1983, Ultimate, ZX Spectrum)

If you owned a ZX Spectrum in the 80s then you undoubtedly knew the name "Ultimate: Play The Game" and associated it with titles that were a cut above their peers. It's less well known that founders Tim and Chris Stamper worked on arcade machines before forming Ultimate (actually just the trading name of the less snappy-sounding "Ashby Computers and Graphics"), but it should come as no great surprise to anyone who has taken even a cursory glance at their debut title JetPac. The multicoloured laser that your character fires is a direct lift from Defender. That the gameplay takes place on a single screen dotted with floating platforms invokes another Williams' hit, Joust. And while I think claims of "it wouldn't look out of place in an arcade" are overselling it somewhat, it's as instantly accessible as the best of them. You could mosey up to it at any time and quickly grasp the gameplay loop: fly around the screen, avoid or shoot the baddies, pick up the rocket parts and fuel until the spaceship starts flashing, then jump in to blast off to the next level. Easy.

JetPac wasn't the first video game I ever played - that honor belongs to a generic Pong console, probably made by Binatone or Grandstand - but it might well be the first I played on a ZX Spectrum. When my dad brought that machine into the house I quickly became obsessed, and it set me down a path of computer geekery that shaped the rest of my life. But I don't think it's just nostalgia that keeps me coming back to JetPac. There are lots of games from that period that I remember fondly but which don't hold up when revisited. But when I set up a Spectrum emulator on a new device - most recently the Anbernic 405m I purchased a few months ago - it's usually the first game I try, more than 40 years after its release in May 1983.

It's a simple game, and you can probably come up with a dozen things you'd add to it off the top of your head right now. Changing the platform layout across different levels is maybe the most obvious, given that the planets that Jetman visits differ only in the type of enemies that reside there. Maybe you'd throw in some power-ups or a two-player competitive mode. But when you realize that this is one of the few games compatible with the short-lived, lower-cost 16k Spectrum, it's impressive that they managed to squeeze so many enemy types and spaceships to build into a memory footprint smaller than most web pages. A tight scope was an inevitability when cramming a game into just 16k, and while there aren't many moving parts to JetPac, they mesh perfectly. The fuel tanks keep the player moving around the screen, the aliens provide danger, the platforms a degree of solace, the bonus items encourage risk-taking in return for higher scores, and the different spaceships grant a sense of progression to the skillful.

Ultimate were always good at working around the Speccy's limitations and playing to its strengths. Colour-clash (a symptom of its inability to display more than two colours within one 8x8 pixel square) is kept to a minimum by careful arrangement of the scenery. And while the original Spectrum wasn't known for its sonic capabilities I do actually like the sound effects, such as they are. Enemies explode not with a boom but with a kind of wet squelch which works with the puffy little cloud that they disappear into. Rose-tinted headphones on my part, perhaps, but effective.

JetPac's simplicity is its strength and why it's a game I keep returning to almost exactly 40 years later. Maybe the controls and many of the enemy patterns - the little fighter jets that hang out at the edge of the screen then dive bomb you are my favourites - are burned into my memory from having played it as a spongy-brained youth. But I can put it down for months... years... and playing it again is immediately enjoyable, like a visit from a childhood friend, without feeling like I have to relearn anything.

A sequel, Lunar Jetman, followed later in 1983. Targeted at 48k Spectrums, it featured a scrolling landscape, a drivable "lunar rover", teleporters, and enemy missile bases that Jetman had to locate and destroy... and wasn't nearly as much fun.

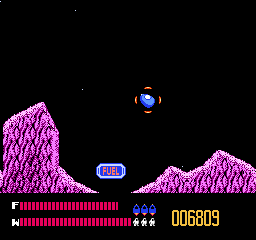

The Stampers sold the Ultimate name in 1985, founded Rare, and abandoned the Spectrum for the more lucrative world of home consoles. I haven't spent enough time with 1990's NES-exclusive Solar Jetman to form an opinion on it, though it has more in common with games like Thrust or Oids than its predecessors.

JetPac may not have spawned a franchise to rival the Marios and Sonics of this world, but it has remained oddly tenacious, thanks to both its fanbase and the Stampers, who throughout the successes of the following decades never forgot their humble origins on that tiny 8-bit computer with the mushy rubber keyboard.

The titular Jetman got his own comic strip in Crash magazine for a while (recently reprinted by Fusion Retro Books.). Donkey Kong 64 (1999) had a Spectrum emulator and a copy of the game hidden in it. Various homebrewed remakes and homages have surfaced over the years, such as Super Jetpak (sic) DX for the GameBoy Color and Jetpac RX which adds to the original Spectrum version.

Finally, 2007 saw the release of Jetpac Refuelled. This Rare-developed reimagining didn't set the world alight, but was good fun, got respectable review scores, and it was rather lovely to see that old Ultimate logo pop up on a game for a modern system. It's just a shame it's still an XBox-exclusive after all these years. Backwards compatibility means that it's still playing on your XBox Series-whatevers even though the 360's online store is closing down, but it would still be nice to see a PC version one of these days. With Microsoft still in possession of Rare and all its IP though, I won't hold my breath.

If you want to play the original JetPac however, and you can't be arsed faffing about with a Spectrum emulator and finding a tape image, you can do so in your browser RIGHT NOW thanks to the Internet Archive!